These personalities were subjects in a series “People of the Past” written and researched by Diana Wall.

Dinah Maria Craik (nee Mulock) (1826 – 1887)

Dinah Mulock, novelist and poet, spent only a short time in Minchinhampton and yet was responsible for the area around the Common, and Amberley in particular, becoming well known in many homes up and down the country over a hundred years ago. She is best remembered for the novel “John Halifax, Gentleman” written in 1856; this rags to riches tale with a strong moral undertone was one of the first works of fiction to become acceptable in Victorian times and was often given as a school prize. A few years after publication it was second only to “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” in a list of the era’s most popular books.

Mr. Thomas Mulock, the novelist’s father, was a reformist preacher working in the area around Stoke on Trent, who married the daughter of a rich widow and Dinah was their eldest child. Her early childhood was spent in a cottage in Newcastle under Lyme and with her two brothers enjoyed imaginative, outdoor games, recounted in a later short story. She attended a day school nearby and recalled how a bout of measles confined the children to bed when she discovered the joy of reading novels. By the age of ten, so her biographer asserts, she had written a long poem about her cat. When she was thirteen Dinah’s grandmother died and the family inherited a portion of her wealth; the decision was taken to move to London and all three children enjoyed a private education. However, Mrs. Mulock’s health began to fail and by the time she was sixteen Dinah had assumed all the housekeeping duties; Thomas, meanwhile, was living the life of a gentleman and invested heavily in railway company stock, which soon failed. When Mrs. Mulock died in 1845 the children were left destitute, as their inheritance could not be gained until each reached the age of twenty-one; their father deserted them completely.

Dinah determined to gain a living by writing, at first fiction for children but progressing to her finest work “John Halifax – Gentleman” in less than ten years. In the novel the hero goes to spend the summer at Enderley (Amberley) where after many vicissitudes he marries and moves to a cottage in the village. This house was most likely Rose Cottage where the novel was written whilst Dinah was staying with the Guild family; some authorities believe she chose the Gloucestershire locations for her book whilst a guest of Mrs. Playne in 1855 – Enderley Mill is Dunkirk Mill owned by the Playnes.

Officially Dinah was Miss Mulock when the book was written, but such was its success in subsequent printings that the author’s name, Mrs. Craik, is now most often used. She married George Lillie Craik, a partner in the Macmillan publishing firm, in 1864. They had no children of their own, but adopted a foundling daughter, Dorothy, in 1871. Dinah continued to write novels, but none achieved the success of “John Halifax – Gentleman”. Such was its popularity that the locations mentioned in the novel attracted visitors and postcards were issued showing Rose Cottage and Enderley Flat (The Common). Even Minchinhampton Market House was described as being “near where Mrs. Craik wrote her famous book.”

The family was preparing for the wedding of Dorothy when Dinah died of heart failure in 1887. However, in this electronic age it is possible to download a copy of “John Halifax – Gentleman” and identify the local landmarks as they were in the Victorian era.

********************

Fenning Parke (1801 – 1872)

Fenning Parke

Not many men love their adopted home so much that they send a card celebrating “a residence of Fifty Years … in Minchinhampton, where most of the … friendships of his life have been formed”. One such man was Fenning Parke, son of a wine merchant of East Smithfield, whose chosen vocation was education. “He left London by Stage Coach at four o’clock on Friday Afternoon, the 28th August 1818, and first set foot in Minchinhampton, at Nine o’clock the following Morning.”

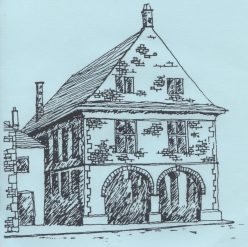

In the early years of the C19th two societies emerged promoting education of the poor: the British and Foreign School Society and the National Society for the Education of the Poor. Both systems were based on the technique of one master educating several hundred children with the aid of partially-educated monitors who passed on their recently acquired knowledge to small groups of ten or so children. David Ricardo was deeply interested in such schooling, and in 1816 established a British School for boys and girls in the Market House. In later life Fenning Parke wrote “In the summer of 1816, Mrs. Ricardo wished to change the system of the Girls’ School from the British to the National. Application was made to the Central School, London for a person to be sent to effect that change – I was selected for that purpose. I came to Hampton in August 1818. The master of the Boys’ School was at that time turning his attention to the clothing business, and I was appointed, by Mr. Ricardo, to succeed him in October 1818, before I was 17 years of age.”

Thus began many years of service to education in the town. In 1824 Fenning married local girl Elizabeth Ogden in Holy Trinity Church, and together they raised a family of two boys and five girls in 33 Tetbury Street, a house owned by the Ogden family. On June 29th 1825 he was appointed by the Vestry as the Parish Clerk, at a salary of £15 per annum, and so started on a long life of useful work for the parish; he later also became registrar. By 1834 the Market House School consisted of 265 boys and girls. There was some degree of overcrowding and a year later he moved the Boys’ School to his house in Tetbury Street, although the girls stayed on in the Market House until the purpose-built school opened in 1868. Children’s schooling was not his only interest and in the 1850’s he was one of the founder members of the Mutual Improvement Association, an organisation which promoted concerts, lectures and other public events in the Market House, as well as providing a reading room in the Lower Island, all designed to improve the education of the working man. He campaigned vigorously for demolition of the cottages that formed Upper Island in the Market Square, seeing this as an improvement to the movement of traffic in the town. Whilst Parish Clerk he collected information on the history of Minchinhampton, recording the inscription on the bells at Holy Trinity, giving lectures on legends and myths, and taking an interest in the old buildings of the town. Many of his notes, poems collected (or possibly written), fliers and open letters survive in the scrapbook of the Improvement Association, held by the Local History Group.

In 1863 his former pupils presented him with a testimonial, in the form of a vellum scroll, a silver inkstand and £100, a true mark of the esteem in which he was held. One wrote a lengthy verse for the local newspapers extolling his teaching career and perpetuating his motto: “Excelsior”. Fenning Parke died in 1872, and is buried along with his wife and two of his daughters to the north of the chancel. As one parishioner stated, “It is not the lot of many men to work so long, so faithfully, and so usefully, in one place, as Mr. Parke was allowed to do in Minchinhampton”.

********************

Charles Robert Baynes (1809 – 1899)

Tucked away behind the cottages in West End lies the beautiful house called “The Lammas” which was for many years the home of Charles Robert Baynes and his family. He was born in Woolwich, the eldest son of a Colonel in the Royal Artillery; indeed at least three of his uncles also served in the army in the Napoleonic Wars. Charles attended Charterhouse School from the age of eleven, but peace had brought an end to a large standing army so, instead of a military career, he joined the East India Company (which controlled the colonies in the Orient on behalf of the Crown) as a civil servant.

The Baynes Family (1895)

It is possible to trace Charles’ career from the excellent records available from the Families in British India Society. In 1828 he was employed as a “writer” or junior clerk at Madras, and whilst there married Jane Moore in 1831. Their four children were all born in India, but Jane died whilst on a passage home to England in 1837. The following year Charles was promoted to assistant judge in Chingleput. He returned home on leave with the children, and in 1841 married his first cousin, Maria Dyneley Hill. After the birth of their first son, she joined him in India, and two daughters and another son were born there. Charles gained further promotion, to a civil and sessional judge and finally to a high court judge in the south of the country. During this time he wrote several legal books, outlining systems of civil and criminal law in India; these are still in print. The Mutiny of 1857 largely took place in northern India, with Madras remaining calm, but following the suppression of the uprising the East India Company was formally dissolved and its ruling powers were transferred to the British Crown. It was at this point that Charles Baynes retired, and returned to England.

What attracted the family to “The Lammas” may remain unknown, but it was to become home until daughter Maria (Mabel) died in 1934. Once settled in Minchinhampton, Charles took a leading part in all matters connected with the neighbourhood; “he had earned his “retirement” … but change of scene with him meant only change of work.” He started and established the “Stroud News and Gloucester Advertiser” in 1867, directing it until 1873 when it was sold to Mr Edward Hulbert. He was active in Minchinhampton too, “with … Mr. Oldfield he was largely instrumental in building (Minchinhampton) schools” as well as being an Inspector for the Lighting District and a founder member of the Fire Brigade Committee, both of which existed in the days before the Parish Council took over local affairs. In 1896 it was reported: “Minchinhampton Fire Brigade proceeded to the Lammas … the men were put through several drills by Capt. Wess and an experiment with the jumping sheet was tried. Capt. Baynes, grandson of Mr. Baynes, jumped from a second storey window of the house and successfully landed in the sheet.”

In 1878 Maria died, but daughters Catherine and Maria lived at home and did not marry; they too followed the tradition of serving the community. Several cousins and other family members moved to the area – to Burleigh, Box and Rodborough, and Charles enjoyed the company of young people, and often visited Minchinhampton Schools and “The Lammas” hosted many family gatherings, especially when his grandchildren visited. The photograph shows him with his youngest granddaughter Daisy in 1895. For more than 25 years he conducted a Bible Class for men in his own home.

Charles was a polished speaker and a staunch conservative. Although his increasing years meant he did not attend Holy Trinity as often as he would have liked, friends always visited and “it was a privilege to hear the good old man recount, in terse and vigorous language, his past experiences, which his retentive memory and unfailing mental faculties enabled him to do”. He passed away in his ninetieth year, at home after “a short and painless illness” and on the afternoon of his funeral every shop was closed, blinds were drawn and the schoolchildren lined the approach to the church. He is buried alongside his second wife, Maria, in the churchyard at Amberley, although there is a memorial window in Holy Trinity, Minchinhampton.

********************

Rose Heseltine Trollope (1821 – 1917)

(Based o an article by Peter Grover)

Behind the existence of a modest gravestone in Holy Trinity Churchyard lies an intriguing story. It marks the last resting place of Rose Trollope, widow of the great Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope, their eldest son, Harry, and Harry’s daughter Muriel. In the adjoining grave lie Harry’s wife Ada and her mother. All died in Minchinhampton.

Rose was the daughter of Edward Heseltine, the manager of a branch of the Sheffield and Rotherham Joint Stock Banking Co.; the family lived above the bank in the High Street in Rotherham. He was one of the town’s leading citizens, and a director of the Sheffield and Rotherham Railway. In the summer of 1842 the family were holidaying in Kingstown, a seaside resort near Dublin, (now Dún Laoghaire) when they met Anthony Trollope, who was working in Ireland for the Post Office. Rose and Anthony soon became engaged, but they did not marry until June 1844 and Anthony later wrote in his autobiography, “Perhaps, I ought to name that happy day as the commencement of my better life”. Both families felt the other socially inferior but “My marriage was like the marriage of other people, and of no special interest to any one except my wife and me”.

Trollope had only just started to write novels, and none was complete when he and Rose moved to Clonmel, in South Tipperary. However, his salary and the travel allowance went much further in Ireland than in England, and the family enjoyed a measure of prosperity. Their two sons, Henry Merivale (Harry) and Frederick James, were born in 1846 and 1847 and Anthony began writing in earnest during the long train trips necessary for his work as a Post Office Inspector. A few years later the Heseltine family was rocked by scandal – the respected bank manager had been making loans for years with insufficient security. A private detective tracked down Rose’s father, who promised to return to Rotherham to explain, but with the threat of legal action he and his wife fled to Le Havre, where he later died.

Rose is believed to have been a model wife – scrupulously honest, faithful, and lastingly affectionate; she was even tolerant of her husband’s too-keen eye for a pretty girl. She advised him on his female characters – such an important feature of Anthony’s stories – even down to matters of dress, and several biographers suggest he modelled some of his characters upon his wife. She carefully checked his manuscripts before publication and kept his financial affairs in order. In 1858 the family moved to Waltham Cross in Hertfordshire and Rose accompanied Anthony on a trip to Boston, U.S.A. in 1861. He was now a famous writer, with a wide circle of literary friends, and fairly prosperous. The family informally adopted Florence Bland, Rose’s niece, who gradually assumed the role of Anthony’s secretary, and it was she who introduced Harry to Ada Strickland, whom he later married.

In 1871, Anthony made his first trip to Australia, with Rose and their cook, on a visit their younger son, Frederick, a sheep farmer near Grenfell, New South Wales. (The modern novelist, Joanna Trollope, is descended from this branch of the family). Once back in England, they made their home in central London, where Anthony continued to write with almost clockwork precision. He returned to Australia three years later, although it is not clear whether Rose accompanied him on this, or his other trips abroad. Anthony’s health had begun to fail, and increasing respiratory complaints led to another move, to the fresh air of Harting on the South Downs in July 1880. Rose stayed in Sussex when he made frequent visits to London; it was at a literary soiree that he suffered a fatal stroke in 1882.

With an inheritance of over £25,000, Rose lived comfortably in Sussex for several years. Harry and Ada, as well as Florence lived in Harting, although none of them appear in the 1891 Census. Were they out of the country? By 1901 Rose and Florence were living in Chelsea, although there is again no reference to Harry or Ada. Circumstances changed in 1908 when Florence died; besides being secretary to Anthony she had become companion to Rose, perhaps repaying the earlier kindness of her aunt. It was then that Rose moved to Greylands in Minchinhampton High Street. By the 1911 Census the household is listed as Harry, his wife Ada, mother Rose, daughter Muriel (the son Thomas was away at school) and three indoor servants, all from the Minchinhampton area. Why the family chose to come to Gloucestershire remains a mystery, as there appear to be no family links on either side. Rose died on May 25th 1917, and lies at peace in our country churchyard.

********************