CHRISTMAS HOSPITALITY – 1543

From 1415 to 1534 the Manor of Minchinhampton and that of Avening were in the possession of the nuns of Syon in Middlesex who used the considerable profits from these agricultural estates for religious good works. However, Henry VIII confiscated these manors following his break with Rome but in 1543 transferred them to Andrew, First Baron Windsor, in exchange for his manor at Stanwell in Middlesex. This was coveted by the King as an addition to the adjacent royal hunting grounds at Windsor. Lord Windsor was no relation to the present Royal Family who adopted the name in the C2Oth and did not wish to exchange but it was clearly an offer he could not refuse.

The C17th historian Dugdale describes the transaction in these words: “Henry VIII sent Lord Windsor a message that he would dine with him, and at the appointed time His Majesty arrived and was received with bountiful and loyal hospitality. On leaving Stanwell His Majesty addresses his host with words, which breathe the very spirit of Ahab. He told Lord Windsor: “that he liked so well of that place that he resolved to have it, but not without a more beneficial exchange.” Lord Windsor answered that he hoped His Highness was not in earnest. He pleaded that Stanwell had been the site of his ancestors for many ages, and begged that His Majesty would not take it from him.

“The King replied that it must be so. With a stern countenance he commanded Lord Windsor, upon his allegiance, to go speedily to the Attorney General, who should more fully inform him of the Royal pleasure. Lord Windsor obeyed his imperious master and found the draught already made of a conveyance in exchange for Stanwell, of lands in Worcestershire and Gloucestershire, and amongst them of the impropriate rectory of Minchinhampton and a residence adjoining the town. (This became known as the Lammas). Lord Windsor submitted to the enforced banishment, but it broke his heart.

“Being ordered to quit Stanwell immediately, he left there the provisions laid in for the keeping of his wonted Christmas hospitality, declaring with a spirit more prince-like than the treatment he had received, that “they should not find it Bare Stanwell”.

It is not recorded whether he found similar provisions laid in at The Lammas, but Lord Windsor did not live long to enjoy his new home and died the following March. To rub salt into the wound he was also ordered to hand over a makeweight payment of £2,297.5s.8d to the King.

********************

TOWN, CHURCH AND MARKET HOUSE – 1698

At the end of the Seventeenth Century Minchinhampton was growing rapidly; an estimated population of 1800 was living in some 350+ houses. The surrounding hamlets of Hyde, Brimscombe, Littleworth and Box (where there were twenty families) accounted for some of these, but the town itself probably contained 1200 people. This extensive parish, as many others in England, was under the dual control of the manor, represented by the Lord of the Manor and his steward, and of the Church, represented by the Rector and the churchwardens, each individually responsible – the one to the Quarter Sessions and the other to the Archdeacon.

For the inhabitants as a whole life moved quietly on as they all went about their daily responsibilities, stepping from their doors directly onto the road, since there were no pavements, and walking along their several streets. West End was almost completely built up and many living there were tenants of the manor, so they occasionally appear in court leet records or in the Sheppard marriage contracts of 1682 and 1718. Tetbury Street was also built with some occupiers recorded as living in the row of seven cottages near the back gate of the White Hart Inn. Friday Street cottages housed some of the tenants of the Rector, as did Parson’s Court, all recorded on the terriers (or Church records). The east side of Butt Street was being built and Well Hill was showing some signs of larger houses. As people moved about the only obstacles they would meet would be horses and other animals, carts and their contents, carriers’ larger vehicles and coaches coming to and from the Manor House. (Some, of course, would use the road from Cirencester and come through the park).

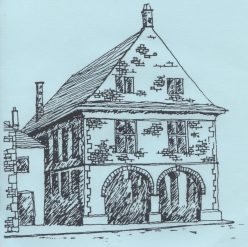

One important object of local gossip would have been the newly erected market house, for the trade in wool and cloth. This was described as being open to the streets on the north (as it still is) and had been built on a large open space with John Panting’s house, soon to be called the Ram, on the east. For the first few years of its existence the new market house was successful, rivalling that at Tetbury and superseding the old market house, or the Upper Island. Lying centrally in what is now known as the Market Square, this had been built by Richard Pinfold; in 1601 he had been given the bailiwick of the market of Minchinhampton with all the tolls of fairs and markets, with the condition that he should build a “sufficient market house.” A little to the west of both these market houses was a plot of land facing down Market Street. Here there were three shops in Richard Pinfold’s day but by 1650 it was waste ground.

Around the High Street the market attracted trade, and many of the front rooms of the cottages were converted into shops or workspaces, the openings to the street being covered with shutters at night. Along Bell Lane, named for the inn that stood there, were the butchers premises or shambles; their shutters formed counters for the display of wares. At the end of the street was the many-gabled, substantial, manor house, with a large garden lying to the north, an extensive group of fine trees and a wide courtyard edged by outbuildings on the south. Philip Sheppard, Lord of the Manor, who commissioned the building of the new Market House, with his wife and his brother Samuel, lived here.

Along Bell Lane was also the most important building for most of the population, the church that they had known since childhood, although their Holy Trinity was not the one we know today, since, in April 1841, the decision was made to take down the nave and chancel and rebuild. Hence a visitor coming to the church in 1700 to see the building described as one of the most interesting in Gloucestershire would find a low entrance porch jutting out roughly central from the south wall. On the east of this was a four-light window, and to the west a two-light one. Also on the west was a flight of stairs, rising to the top of the porch and ending at a door. If he had gone round the west end of the church he would have found similar stairs and doors. Entering by the porch door he would have found the reason for these; above his head was the south gallery and immediately opposite another. A third was on the west wall, erected in 1670 by the churchwardens, and the front half of the chancel also held a gallery. The whole of the nave, the galleries and part of the chancel were occupied by box pews or seats each belonging to a private individual or a property, and which could be bought or sold! Trade in the early 18th century was not confined to wool or staple commodities!

********************