The manor remained under the control of religious houses until the Dissolution of the Monasteries and shortly afterwards, in 1543, Henry VIII forced Andrew, First Baron Windsor, to give him the estate of Stanwell in Middlesex in exchange for Minchinhampton. In 1656 Samuel Sheppard purchased the property, enlarging the house of the steward near the church. The Gloucestershire historian Sir Robert Atkyns describes the house and “a spacious grove of high trees in a park adjoining to it, which is seen at a great distance.” An engraving by Kip illustrating this account shows a typical Cotswold gabled, stone-built house with a walled pleasure ground almost surrounding it. The park to the north had been demesne land belonging to the Lord of the Manor.

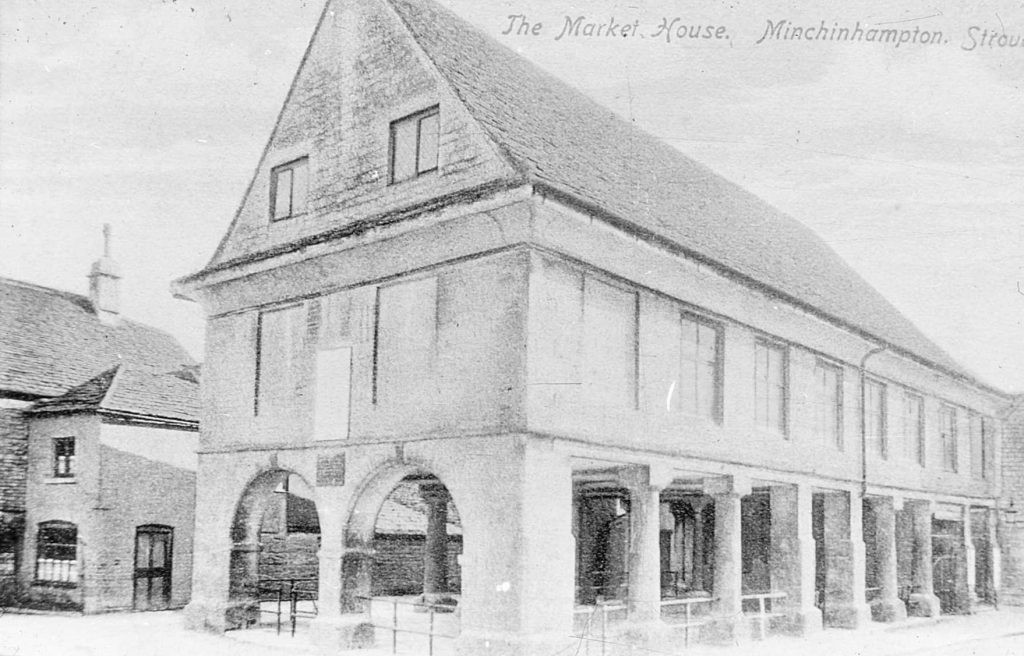

Another member of the Sheppard family, Philip, built the Market House in 1698. Samuel Rudder described Minchinhampton a century later: “Within the parish, is a little town of the same name, with a market on Tuesdays, and two fairs in the year viz. one held on Trinity Monday, and the other on the 29th of October … The town consists of four streets, in the form of a cross, with three market houses, one of which was built in the year 1700 (sic) for storing of wool and yarn, in expectation of establishing a great mart for those commodities, as the town is well situated for that purpose in a great clothing country; but it seems not to have fully answered the design”

Minchinhampton is an excellent example of a small Cotswold town. Many of the buildings date from the C17th and C18th; these were the great days of the woollen cloth industry that saw the area assume a national importance. In the 1790s there was rapid growth due to the expansion in hand weaving, and at least seventy cottages were built on land taken from the common between Rodborough and Box at this time. Gradually the open stalls of the Tuesday market gave way to more permanent shops. There is evidence that the butchers’ shambles were located along the southern side of the churchyard, and most of the shops were positioned in the High Street (as they are now!) The cruciform pattern of the main streets relates to the crossing of two roads, from Stroud south to Tetbury and Bath and east to Cirencester and London.

In addition to the trade in wool, a demand grew for the Oolitic Limestone, and there is abundant evidence of local quarrying. Farm produce also found a ready market in the growing cities of industrial England. When first the canal, then the new turnpike road and finally the Great Western Railway were constructed in the Golden Valley, Minchinhampton lost its locational advantages, but lack of growth meant that many of the older houses have remained unencumbered by Victorian additions. In the High Street are the crooked gables of the former White Hart, and opposite the fine Greylands, which was once home to the widow of Anthony Trollope. The Cotswold Club, though much altered, is a C17th house, and even earlier are Arden House and Arden Cottage, with the archway between them showing carved Tudor roses.

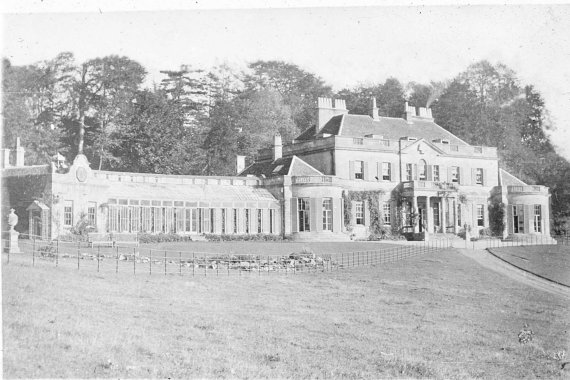

By the mid-eighteenth century the Sheppard family, whose memorials can be seen in the churchyard, found their mansion to be draughty, outdated and difficult to maintain. Edward Sheppard chose to build a new house for his family at Gatcombe Park in 1774, preferring the rural location to that of his old property in the centre of Minchinhampton, thus distancing himself from the day-to-day affairs of the town, as did many of his contemporaries elsewhere in Gloucestershire. In the early C19th is was stated that Gatcombe “is placed on the ascent of a narrow valley, bounded by high beech wood … The house looks down on a spacious and fine lawn, which terminates in waters, expanded by the hand of art to an ornamental breadth of space. The present elegant house is a well-proportioned and spacious mansion, handsome on the exterior and internally well designed and arranged”.

The building costs of the new mansion were, however, a drain on the resources of the Sheppard family, and Gatcombe Park passed out of their hands into those of the Ricardo family, who continued as Lords of the Manor into the twentieth century. George Basevi, who was also responsible for the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, designed the curving conservatory for David Ricardo, the eminent economist; this distinctive feature is recognised by all those who attend the three-day events held in the park by the current owner, H.R.H. the Princess Royal.