The town stagnated during the Nineteenth Century when bypassed by the main transport links and the fortunes of the area were also affected by the decline in handloom weaving, which had been the home industry in many of the older cottages. This had led to economic distress amongst the weavers, and the records of the early C19th catalogue a decline in income, partly due to the blockade of English shores by Napoleon, then to the appearance of weaving shops in the mills of the valleys. By 1839 Longfords Mills had ninety handloom weavers and one power loom and Dunkirk had seventy-one handloom weavers and two power looms. There were protests about the latter, and Abraham Smith of Box was said to have “riotously and tumultuously assembled with a great concourse of people and threatened to do Thomas Marling some bodily injury” in 1825.

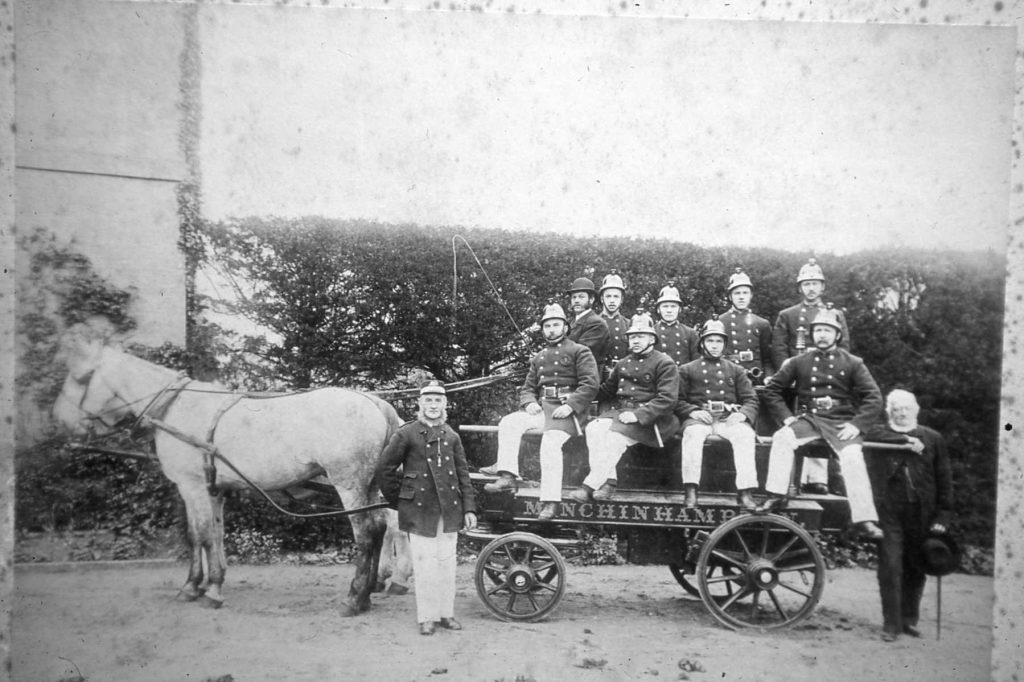

The conditions were such that many people were tempted to try to gain a better life abroad and between 1839 and 1842 nearly fifty Minchinhampton weavers emigrated. A century previously the responsibility of caring for the poor, levying a poor rate and the repair of the highways were laid upon local vestries. These developed from parish meetings, which consisted of all the male church members who met once a year to elect churchwardens. The ecclesiastical work of the vestry had become submerged in the concerns of the town and tithing, the rural neighbourhood, and the meetings usually consisted of a few men who were concerned with a particular issue, but the name was retained. However, even though unelected, the Minchinhampton Vestry carried out considerable improvement work in the C19th including the provision of a fire engine, lock-up, gas lighting and purchasing one of the cottages in the churchyard for the Sunday School.

The site of the old manor house had been sold during the Napoleonic Wars, and in the early 1820s a certain William Whitehead conceived the idea of building himself a mansion, to be called Minchinhampton Abbey, on its site. Foundations were laid, the walled garden set out, but he managed to lose a fortune at the gaming tables and the land was sold to David Ricardo, thus completing the circle of ownership. It was the Ricardo family who donated the land on which the first Minchinhampton Schools were built in 1868, having established a school in the Market House fifty years earlier. The present school is the third on the site, the last one having survived just thirty years from 1968. In Bell Lane, so called not for the church bells but from an inn that stood there, is the Master’s House, built at the same time as the original school.

Throughout the Victorian period conditions for the inhabitants of Minchinhampton gradually improved. The remaining stretches of open fields had been enclosed and many farms required labour, especially to the east of the town. Many women found work in the spinning mills of the valleys, and their menfolk accepted employment on the power looms. Other mills made walking sticks and umbrella frames, and new engineering industries could be found at Brimscombe, Thrupp and Nailsworth. The small cottages in West End, Tetbury Street and lower Butt Street became home to larger families, as more children survived infancy, and vegetables from the garden, where a few chickens and possibly a pig would be kept, supplemented the diet. Just below the spring that gave Well Hill its name is King Street; this was once the poor end of town and the row of cottages has date stones, more recent as you ascend the hill.

By the 1880s Tetbury Street was home to many craftsmen, without whom a settlement such as Minchinhampton could not survive. Apart from the building trades, including tilers and plasterers, carpenters and a gas fitter, there was a master cabinetmaker employing two apprentices living on the north side of the street. Associated with transport there were a wheelwright (with another who described himself as retired), a saddler and harness maker and a blacksmith, and another forge was to be found in Butt Street. The trade directories of the time suggest that the chimney sweep and the coal dealer carried on their work from their cottages in Tetbury Street, as did three dressmakers and two milliners

Holy Trinity Church remained the focus for a large proportion of the population, and a comprehensive rebuilding exercise was carried out on the chancel and nave, which had been in danger of collapse. However, the Baptist Chapel was completed in 1834 to replace the smaller meeting-room in Workhouse Lane, which was converted for use by the Sunday School. By the end of the Victorian period the church was strong both numerically and spiritually, with many members living close by in Tetbury Street, the non-conformist creeds having a great appeal to working men and women. . Sunday School was a way of furthering the general education of adults who worked all week, and was enthusiastically encouraged by Anglicans and Baptists alike. Concerts, plays and readings were regularly held in the Market House, and the Mutual Improvement Association organised a series of lectures in the mid C19th, all designed to improve the life of the working man or woman.

There were, of course, less serious diversions for the growing population. The Whitsun Fair had evolved into two parades, held by the Anglican and Baptist churches, culminating in tea and sports on the Great Park, and, later, a free ride on the roundabout set up there. The Rogers family brought their travelling funfair to the commons for at least eighty years, at first using steam traction engines, of which several pictures exist. Sometimes all the non-conformists of the area met together; on one occasion nine Sunday Schools assembled, with nearly nine hundred children present, accompanied by two bands of musicians and around a thousand spectators. One of the bands was probably the Minchinhampton Town Band, which regularly practised in the Market House.

By the end of the C19th there were slightly less decorous gatherings at the many public houses within the town, several of which were supplied from Playne’s Brewery at Forwood. The congregation of the Baptist Church became so concerned that early in the C20th the Institute was built on their land, as a meeting place for the men of the town, where no alcohol would be served!